SCREENED: THOUGHTS ON INVISIBILITY

by Benedetta Casagrande

31.10.2016

"Images are mediations between the world and human beings. Human beings “ex-ist”, i.e. the world is not accessible to them and therefore images are needed to make it comprehensible. However, as soon as this happens, images come between the world and the human beings. They are supposed to be maps but they turn into screens: instead of representing the world, they obscure it until the human beings’ lives finally become a function of the image they create." - Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography

Photography traffics in illusions, but among its distortions still seems to offer a kind of contact with the world. In the act of looking at photographs, the photograph recedes, becomes transparent, a window or portal in time. What disappears in that moment is the infrastructure of photographic technology itself: for the eye that looks upon the world, it is the eye itself that cannot be seen. Yet in the persuasiveness of their detail, photographic resemblances always seem to seduce us back into a naive realism: we do not look at photographs, but through them.

For Vilém Flusser, the photograph, as the first ‘technical image’, fundamentally transformed the way in which we relate to the world. “The invention of photography constitutes a break in history that can only be understood in comparison to that other historical break constituted by the invention of linear writing.” In opposition to the traditional image, Flusser describes the technical image as an abstraction of a third order: it is an abstraction from text, which is an abstraction from the traditional image, which is in itself abstracted from the concrete world. Rather than a means of representing the world, photographic technology becomes a way of constituting it. But the means by which the camera apparatus does this are not shaped by the photographer, who in Flusser’s account becomes a simple functionary of a pre-formatted programme:

"The photographer’s gesture as the search for a viewpoint onto a scene takes place within the possibilities offered by the apparatus. The photographer moves within specific categories of space and time regarding the scene: proximity and distance, bird- and worm’s-eye views, frontal- and side-views, short or long exposures, etc. The Gestalt of space–time surrounding the scene is prefigured for the photographer by the categories of his camera. These categories are an a priori for him. He must ‘decide’ within them: he must press the trigger."

Photography traffics in illusions, but among its distortions still seems to offer a kind of contact with the world. In the act of looking at photographs, the photograph recedes, becomes transparent, a window or portal in time. What disappears in that moment is the infrastructure of photographic technology itself: for the eye that looks upon the world, it is the eye itself that cannot be seen. Yet in the persuasiveness of their detail, photographic resemblances always seem to seduce us back into a naive realism: we do not look at photographs, but through them.

For Vilém Flusser, the photograph, as the first ‘technical image’, fundamentally transformed the way in which we relate to the world. “The invention of photography constitutes a break in history that can only be understood in comparison to that other historical break constituted by the invention of linear writing.” In opposition to the traditional image, Flusser describes the technical image as an abstraction of a third order: it is an abstraction from text, which is an abstraction from the traditional image, which is in itself abstracted from the concrete world. Rather than a means of representing the world, photographic technology becomes a way of constituting it. But the means by which the camera apparatus does this are not shaped by the photographer, who in Flusser’s account becomes a simple functionary of a pre-formatted programme:

"The photographer’s gesture as the search for a viewpoint onto a scene takes place within the possibilities offered by the apparatus. The photographer moves within specific categories of space and time regarding the scene: proximity and distance, bird- and worm’s-eye views, frontal- and side-views, short or long exposures, etc. The Gestalt of space–time surrounding the scene is prefigured for the photographer by the categories of his camera. These categories are an a priori for him. He must ‘decide’ within them: he must press the trigger."

On one side of the lens, the apparatus of the camera and its internal, unexplored space in which reality is introjected and enclosed. On the other, the source material which results in the derivative product of the photograph. Big Sky Hunting by Alberto Sinigaglia, Untitled (Two Figures) by James William Murray and Camera by Seán Padraic Birnie each enter into conversation in this uncertain space, creating an inverted projection of the apparatus and its hallucinatory potential.

Bringing the concealed body of the apparatus into view, “World” (from Camera) examines the interior space of the camera body to illuminate the obscurity at the heart of photographic production. The lens is removed and the device sealed from the outside world, interrupting the flow of light which puts exterior and interior in dialogue. In the sealed interior of the body, the sensor, primed for light and vision, records a landscape of noise and no signal. This results in an abstract space constructed by noise and invisibility. Yet, a certain familiarity is evoked by the fading landscape. The abstract image recalls the infinite horizons of landscapes and seascapes that inhabit our collective memory.

In “Camera ii.” (from Camera), the photographed lens appears as a bottomless void in which the viewer is absorbed. Looking through the body of the camera, obscurity becomes a site of absorption and perdition, enclosing an infinite combination of possibilities - in the impenetrable night the human mind seeks familiar shapes to define an imaginary space. In a condition of semi-blindness, the mind is forced to rely on both memory and imagination to construct meaning. The allure of the unseen (and hence unknown) exacerbates the relevance of the relationship between obscurity and visibility in the dynamics of the photograph.

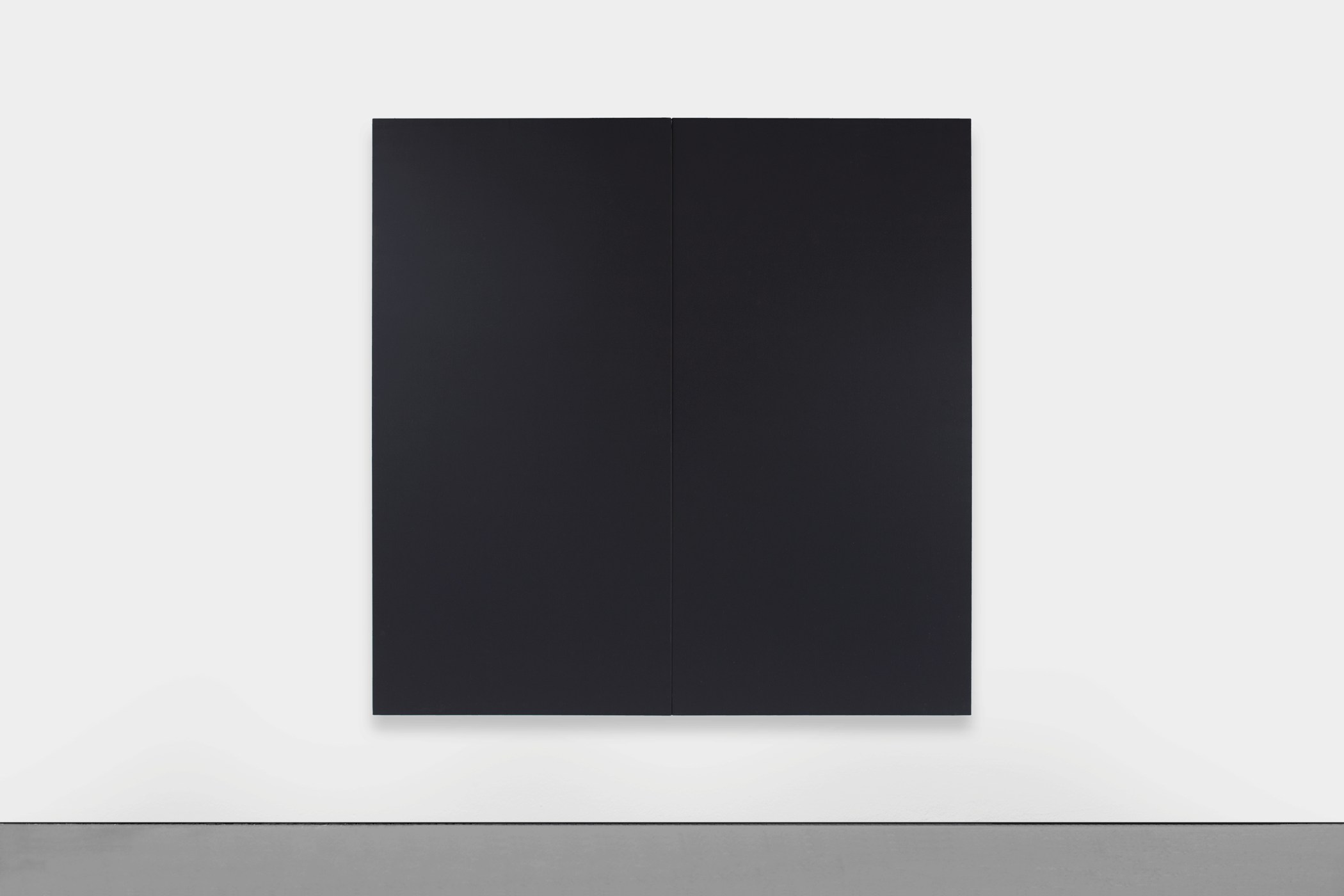

James W. Murray’s Untitled (Two Figures) consists of a sculptural piece comprising two adjacent screens made out of blackout fabric, traditionally used to obscure the dark room. Untitled (two figures) solicits desire through invisibility, questioning and exploiting the paradoxes found in the etymological history of the screen. Because ‘screen’ is a paradoxical word: in Skeat’s Etymological Dictionary, the word has been described as ‘that which shelters from observation, a partition’ and ‘a coarse riddle or sieve’, implying that the two main uses of the word refer to sheltering from observation and partitioning. As a sieve would retain thicker elements whilst allowing the thinner elements through, the screen serves as metaphor for both hiding and revealing. By separating elements, the screen provides the order that sometimes comes from separation, allowing the audience to focus only on that which is being revealed, momentarily silencing the unnecessary and leaving the attention uncluttered. The questions which naturally arise are simple but fundamental in our understanding of Murray’s piece and its relevance in this exhibition: who or what is being sheltered? Who is it being sheltered from? As an audience, on which side of it do we stand? And mostly: in what ways does the impossibility of vision stimulate our deepest curiosities and desires? In many ways, Murray’s piece functions as a Pandora’s box, endlessly alluring in its unveiled secrecy. Putting in play the relationships between presence and absence, visibility and invisibility, Murray highlights the importance of these paradoxes in our understanding of the visual arts.

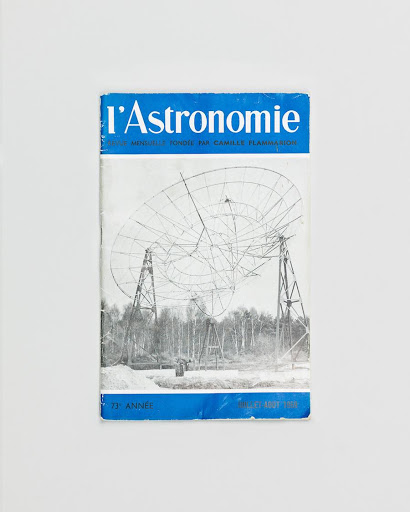

Alberto Sinigaglia's Big Sky Hunting balances the exhibition by "presenting a journey to the limits of representational space". Exploring the relationship between man and space, and more specifically the urge to dominate and control space, Big Sky Hunting confronts us with abstract and semi-scientific images sourced from his surroundings. Appropriating and manipulating various elements including original photographs and archival documents, Sinigaglia comments on the human desire to make comprehensible what cannot be understood. Big Sky Hunting places the emphasis on the human mind’s capacity to create and imagine that which it wants to see, or better yet, that which it desires in order to create a protective shell; a reassuring barrier inside of which that which is known, or may be known, can be controlled.

Sinigaglia’s project reminds us of the most fascinating mechanisms of our psyche; the need for dominance, control and understanding, or in other words the need for safety. Our use of photographic media reflects our need to control and understand the world. And the language associated with photography asserts a human dominance over space: we ‘capture’ our surroundings, we ‘immortalize’ our lovers, we ‘take’ photographs as if in doing so we have removed something from the world.

Overall, SCREENED delves into the maze of perception, exploring the fantastical potential of photographic media and, more importantly, the deepest ways we relate to it. In bringing together three artists who are each in their own ways engaged with questions of visibility, medium and technology, the exhibition invites the audience to fantasize, reflect and get lost within the bottomless depths of photographs. The installation offers an overall sense of physicality, by combining the use of sculptures with images. The viewing is essential. The core of this work offers an experience to the viewer through the reflection of light on the surface of the objects and on the images, wrapped by a plastic sheet. In this scenario, the referential content of the image loses significance, becoming barer of perception rather than of indexical content.

Sinigaglia’s project reminds us of the most fascinating mechanisms of our psyche; the need for dominance, control and understanding, or in other words the need for safety. Our use of photographic media reflects our need to control and understand the world. And the language associated with photography asserts a human dominance over space: we ‘capture’ our surroundings, we ‘immortalize’ our lovers, we ‘take’ photographs as if in doing so we have removed something from the world.

Overall, SCREENED delves into the maze of perception, exploring the fantastical potential of photographic media and, more importantly, the deepest ways we relate to it. In bringing together three artists who are each in their own ways engaged with questions of visibility, medium and technology, the exhibition invites the audience to fantasize, reflect and get lost within the bottomless depths of photographs. The installation offers an overall sense of physicality, by combining the use of sculptures with images. The viewing is essential. The core of this work offers an experience to the viewer through the reflection of light on the surface of the objects and on the images, wrapped by a plastic sheet. In this scenario, the referential content of the image loses significance, becoming barer of perception rather than of indexical content.

info@ardesiaprojects.com