FOLK —AARON SCHUMAN

by Benedetta Casagrande

30.03.2017

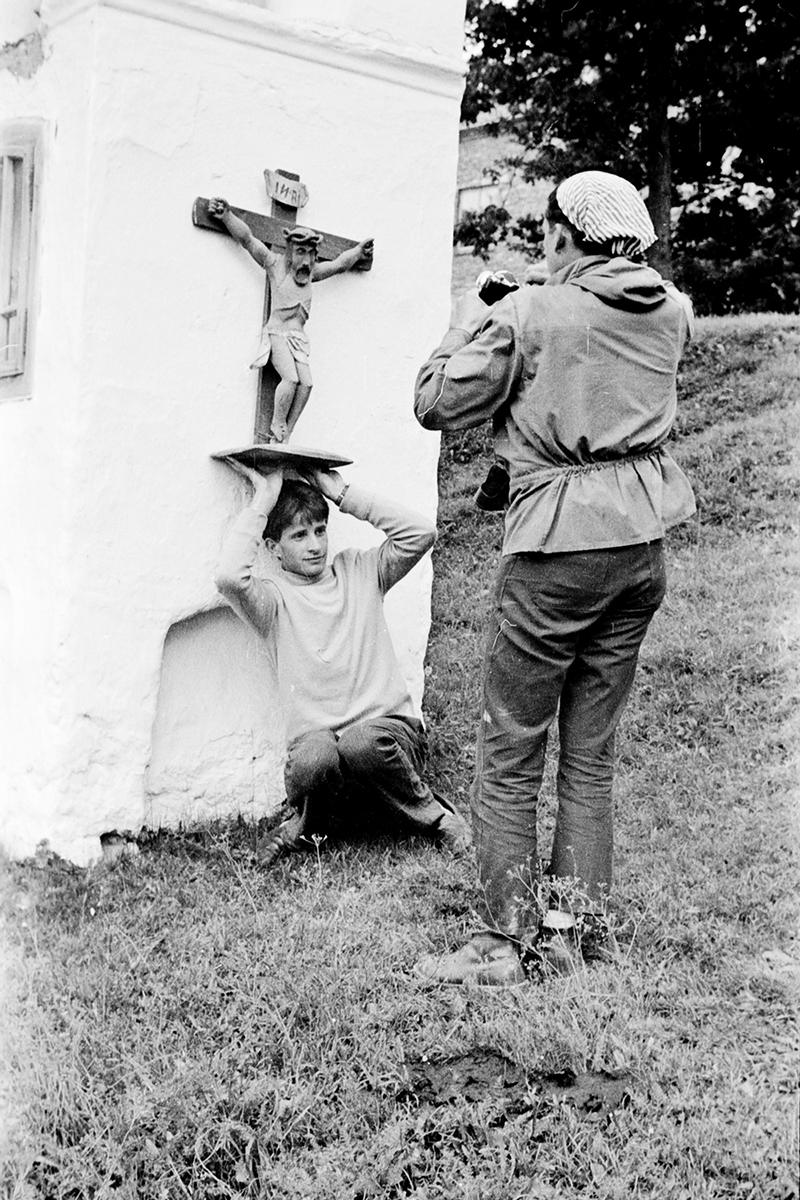

Published in July 2016, the photobook Folk by Aaron Schuman traces the photographer’s investigation into his Polish heritage. This journey of reconnection and re/search into his cultural roots sets off with a close-knit collaboration with the Ethnographic Museum of Krakow and it’s team of curators, researchers and coordinators, which became his main guide into the understanding of local customs and traditions to map his own personal cultural origins. Yet, to understand the book as a mere investigation into his own family’s cultural background would be a limited understanding of what his photobook does: during his ethnographic research Schuman uncovers not only his long-gone connection to the local land, but more importantly focuses on the process of preservation of local traditions and the relationship between the “museum folks” and their determination to arrest the disappearing transmission of cultural beliefs from generation to generation.

As a fourth-generation Polish-American, Schuman was confronted with materials which were “both vaguely familiar and also very exotic and foreign”, as explained by him in an email to the Festival director of the museum. This feeling is palpable throughout the project, which still transpires a certain fascinated distance between the photographer and the observed materials. Under a point of view of aesthetics the images appear heimlich, in that they succeed in evoking a sense of simultaneous familiarity and lack of familiarity. Freud suggests the word heimlich is “not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on one hand it means what is familiar [...] and on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight”, hence unknown.

Not unlike Adam Fuss’ photograms, some of the images within Folk come back to haunt us, stimulating memory and certain natural associations tied to Pagan rituals and the cult of the land, such as the sickle and the hand-cut wooden dolls. The ethnographic portraits of the locals' traditional costumes exercise the same effect, bringing back into daylight gone women which belong to the collective imaginary but that undoubtedly existed in the palpable world. Thanks to the presence of new color images taken by the photographer, the book weaves a tapestry which takes us back and forwards in time, allowing us both to dive into the mysteries and narratives of Polish traditions and into their direct existence in our contemporary life. This symposium of images invites us to participate in the hunt, allowing us to feel the thrill of that very process of discovery and preservation which is at the heart of the work of both the Ethnographic Museum and the photographer himself.

As a fourth-generation Polish-American, Schuman was confronted with materials which were “both vaguely familiar and also very exotic and foreign”, as explained by him in an email to the Festival director of the museum. This feeling is palpable throughout the project, which still transpires a certain fascinated distance between the photographer and the observed materials. Under a point of view of aesthetics the images appear heimlich, in that they succeed in evoking a sense of simultaneous familiarity and lack of familiarity. Freud suggests the word heimlich is “not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on one hand it means what is familiar [...] and on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight”, hence unknown.

Not unlike Adam Fuss’ photograms, some of the images within Folk come back to haunt us, stimulating memory and certain natural associations tied to Pagan rituals and the cult of the land, such as the sickle and the hand-cut wooden dolls. The ethnographic portraits of the locals' traditional costumes exercise the same effect, bringing back into daylight gone women which belong to the collective imaginary but that undoubtedly existed in the palpable world. Thanks to the presence of new color images taken by the photographer, the book weaves a tapestry which takes us back and forwards in time, allowing us both to dive into the mysteries and narratives of Polish traditions and into their direct existence in our contemporary life. This symposium of images invites us to participate in the hunt, allowing us to feel the thrill of that very process of discovery and preservation which is at the heart of the work of both the Ethnographic Museum and the photographer himself.

The range of images presented creates a parallel between his own photographic practice and the practice of the museum’s team. Focusing on the specific items involved in the accumulation and categorisation of ethnographic material - which include photographs understood as objects and tools which gain significance thanks to their physical use and handling - the project highlights the relevance of the ethnographic photograph understood as material object with a specific social value. John Tagg argues in his model of “currency of photography” that “items [were] produced by a certain elaborate mode of production and distributed, circulated and consumed within a given set of social relations: pieces of paper that changed hands, found a use, a meaning and a value, in certain social rituals.” This model gives equal weight to representational content and to the use value by which images were accumulated, exchanged and exhibited giving them social value.

In her essay Material Beings: Objecthood and Ethnographic Photographs Elizabeth Edwards highlights that “such questions [concerning materiality] also allow us to consider differently the performative, phenomenological and experiential qualities of photographs and their social biography as socially salient objects moving through space and time”. By interacting directly with the photographic materials of the Ethnographic Museum rather than only with it’s archival objects Schuman increases the social value of the photo-objects. This contribution is augmented by the production of new photographs taken by the photographer; by producing new images of the archive Schuman contributes the expansion and re-contextualisation of the tradition of the anthropological archive, allowing a fresh interaction with the archival material.

In her essay Material Beings: Objecthood and Ethnographic Photographs Elizabeth Edwards highlights that “such questions [concerning materiality] also allow us to consider differently the performative, phenomenological and experiential qualities of photographs and their social biography as socially salient objects moving through space and time”. By interacting directly with the photographic materials of the Ethnographic Museum rather than only with it’s archival objects Schuman increases the social value of the photo-objects. This contribution is augmented by the production of new photographs taken by the photographer; by producing new images of the archive Schuman contributes the expansion and re-contextualisation of the tradition of the anthropological archive, allowing a fresh interaction with the archival material.

At the end of the book we find the emails exchanged between the photographer and the “museum folks”, which reveal a set of relations born through the making of the project and which highlight how the project reverberated through every subject involved in the making of it. In the painstaking attempt to reconnect with his own origins, Schuman admits that his “family’s past, although present, seemed distant, muffled, and very faint” and that he “still felt like a stranger to the place”. Despite this failed connection with the landscape, Schuman found his “folk” amongst the researchers and ethnographers of the museum which, on their side, reconnected with their own personal stories, stimulated by Schuman’s research.

The book closes with an email by Magdalena Zych, museum research coordinator, which uncovers the story of a coral-bead necklace passed down by the women in her family, giving her the impression that “they are a little bit here, among living people''. Schuman’s work gracefully pierces through the layers of history inviting us to come closer to the many complex aspects of ethnographic archival photographic materials and the research processes that precede them, allowing us to experience the most exciting aspects of research and the discovery which comes with it. The photo book sheds light on the most tender aspects of the drive for knowledge and preservation: memory, our temporality, and the attempt to understand one’s own identity through the exploration of anthropological objects, powerful in their social value which reverberate old-gone traditions into today's worlds.

![]()

The book closes with an email by Magdalena Zych, museum research coordinator, which uncovers the story of a coral-bead necklace passed down by the women in her family, giving her the impression that “they are a little bit here, among living people''. Schuman’s work gracefully pierces through the layers of history inviting us to come closer to the many complex aspects of ethnographic archival photographic materials and the research processes that precede them, allowing us to experience the most exciting aspects of research and the discovery which comes with it. The photo book sheds light on the most tender aspects of the drive for knowledge and preservation: memory, our temporality, and the attempt to understand one’s own identity through the exploration of anthropological objects, powerful in their social value which reverberate old-gone traditions into today's worlds.

info@ardesiaprojects.com